When terrestrial animals migrate collectively in a certain direction, it’s called “migration.” For aquatic animals, when they gather and move towards a particular area, it’s termed “migration” as well. In fact, the biological significance of migration and dispersal is essentially the same. From the widespread phenomenon of collective activities among animals, we can easily observe that group living tends to be more beneficial for both species preservation and individual survival. Therefore, when animals reach a critical period or important stage in their lives, they instinctively gravitate towards group living. This is an instinctual behavior. Otherwise, not only would individual survival be at risk, but the possibility of species preservation would also be compromised.

The migration of aquatic animals, although it can be divided into three forms: reproductive migration, foraging migration, and overwintering migration, is essentially centered around species preservation.

Aquatic animals generally undergo external fertilization. Both males and females release sperm and eggs into the water, where they come into contact and fertilize each other to form embryos. Shallow waters near the shore are more stable and conducive to fertilization. Additionally, they receive ample sunlight, resulting in higher water temperatures and faster embryo development. Therefore, aquatic animals typically utilize the period when sunlight is strongest, around late spring to early summer, to migrate in large groups to nearshore areas to complete mating and spawning tasks. This phenomenon is known as “reproductive migration.” For example, during the mating season, Atlantic herring can turn the seawater near the coast of Norway milky white due to the abundance of sperm and the size of the fish shoals, indicating the successful completion of ovulation and fertilization.

As for foraging migration, upon closer examination, it becomes apparent that it occurs after the reproductive period when the fish bodies have been severely depleted, necessitating a peak foraging period to compensate for losses. For example, the winter migration of ribbon fish in the Zhoushan fishing ground is a scene of fish foraging migration that occurs every winter.

On the surface, overwintering migration may seem to be solely driven by decreasing water temperatures and reduced food availability. In reality, it also serves as a physiological adjustment for body maintenance during hibernation and preparation for the next spawning and sperm release, thus creating conditions for reproduction in the following year. Therefore, the entire life of an animal revolves around species preservation.

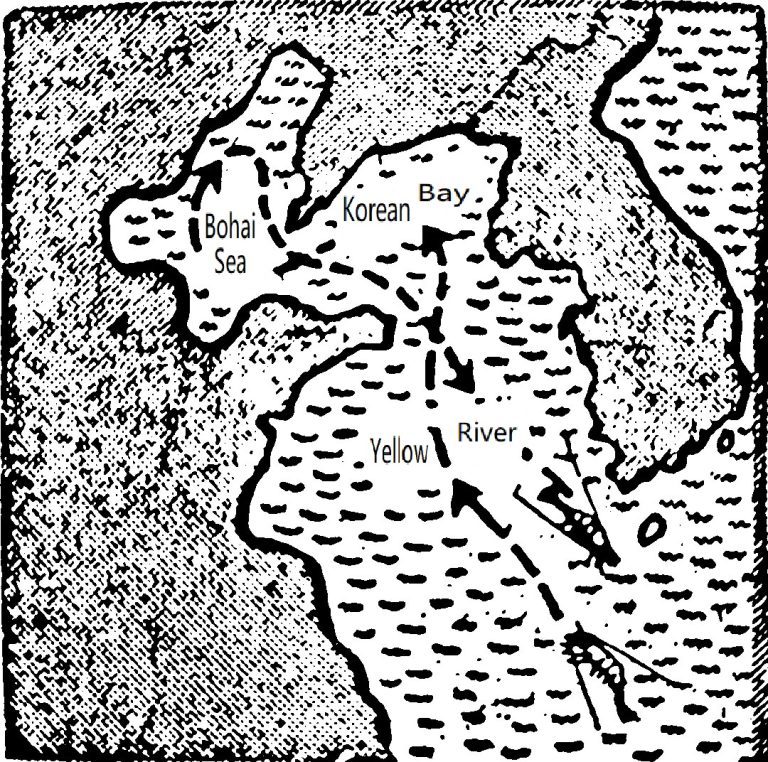

Shrimp’s migratory activities are no exception. They typically depart from the deep-sea areas of the southern Yellow Sea around March each year, and from April to the end of June, they gather near the estuaries of the Bohai Sea and the Korean Bay to spawn. Thus, this migration is reproductive in nature for shrimp. After spawning, they disperse to coastal areas to forage. As the weather gets colder and food becomes scarce around late autumn and early winter, they begin to gather and migrate towards deeper waters. Then, they form large groups and return to the deep sea off the southern coast of the Shandong Peninsula to overwinter through the Bohai Strait. Therefore, the migration of shrimp from October to November each year is considered overwintering migration.

Currently, we have mastered the annual cycle of shrimp activities, their migration patterns, and routes. Along their migration routes, we organize two large-scale fishing expeditions every year. The Shidao fishing ground on the Shandong Peninsula is the largest base for shrimp fishing.