Do you know how much water plants consume throughout their lives? Here’s a number for you: during their growth period, plants absorb water equivalent to 300-500-800 times their own weight. For instance, if a plot of land yields 500 jin (a Chinese unit of weight) of wheat, including stems and roots totaling 2000 jin, their water requirement (calculated as 300 times the dry yield) would be 600,000 jin per mu (a Chinese unit of area).

Plants absorb water from the soil. But how does the soil supply water to plants?

Essentially, although the soil near the roots is moist, as plants rapidly absorb water, the upper layers of soil near the roots quickly deplete their water content. At this point, water must be supplied from deeper soil layers, where soil continuously transports water from different layers to the vicinity of the roots. To facilitate this, there must be a force capable of moving water and even lifting a considerable amount of water to the upper soil layers.

This force is known as capillary action. Soil, being porous, contains numerous capillary spaces through which water rises to certain heights and distributes throughout. Different soils have varying capabilities to supply water; denser or finer soils with fewer large gaps transport water more quickly to the roots of plants.

We can observe this phenomenon through experiments.

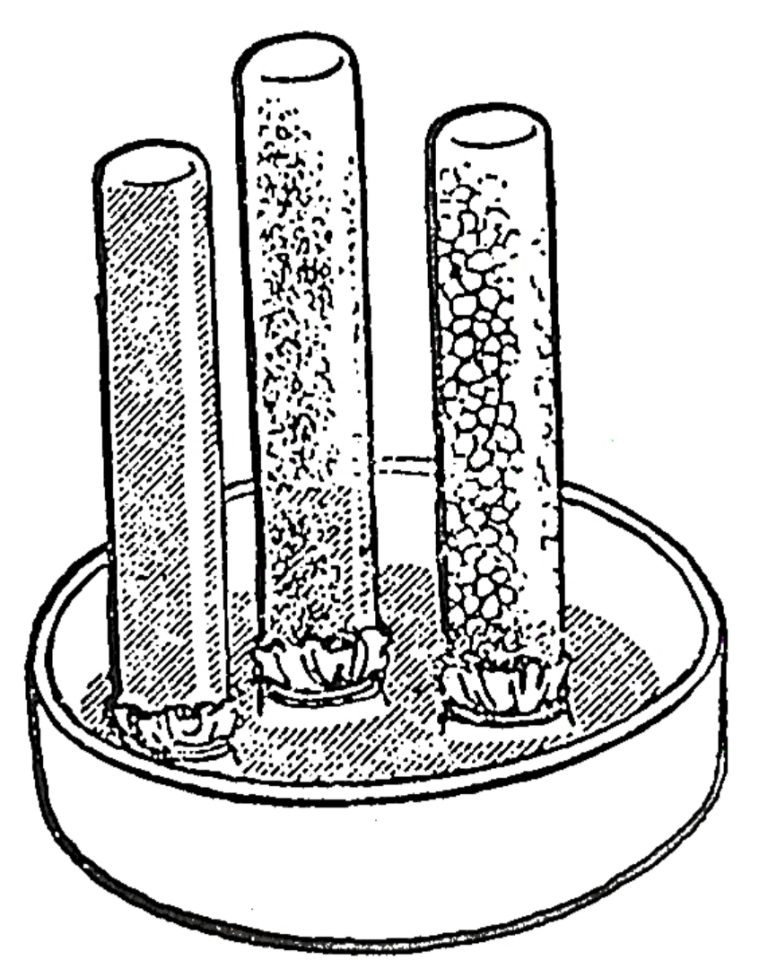

Prepare three identical glass tubes closed at one end and open at the other, along with a tray. Fill the three tubes with different types of dry soil (finest, medium-coarse, and large-grain soil), covering one end with cloth. Place these tubes upright in the tray filled with water (with the cloth-covered end facing down). By observing the color difference between moist and dry soil, we can see water rising through the soil. Additionally, the varying capillary actions of different soil textures become evident.

If clarity is needed, modify the experiment slightly by substituting the water in the tray with flammable liquids like kerosene or alcohol, allowing you to ignite the “wicks” made of soil. You will observe that the flames produced by soils of different textures differ in size: the finest soil produces the largest flame, followed by medium-coarse soil, and the largest-grain soil produces the smallest flame.

By analyzing flame sizes, we can assess soil structure, its degree of looseness, and its effectiveness in supplying water.